January 15, 2018

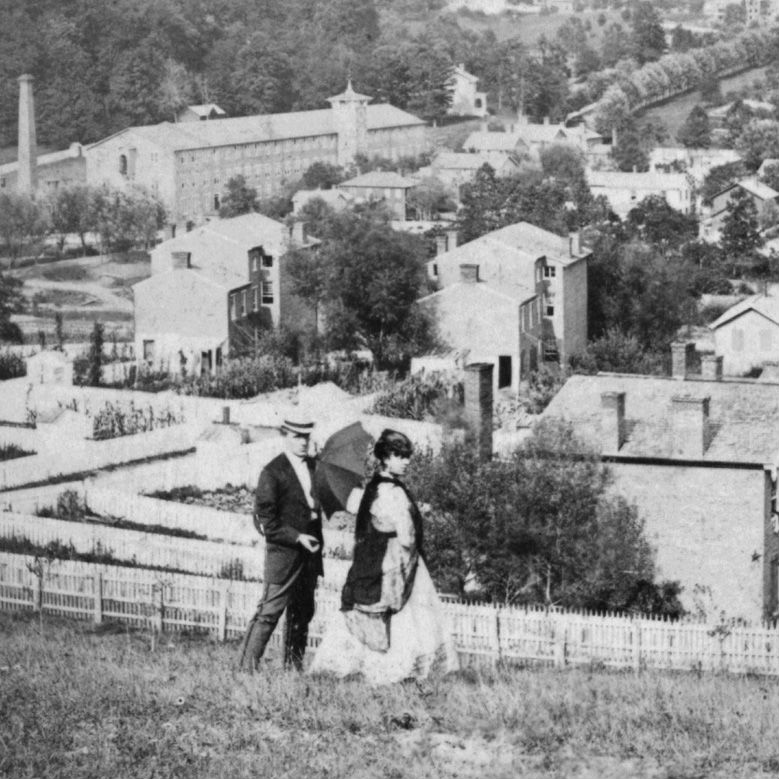

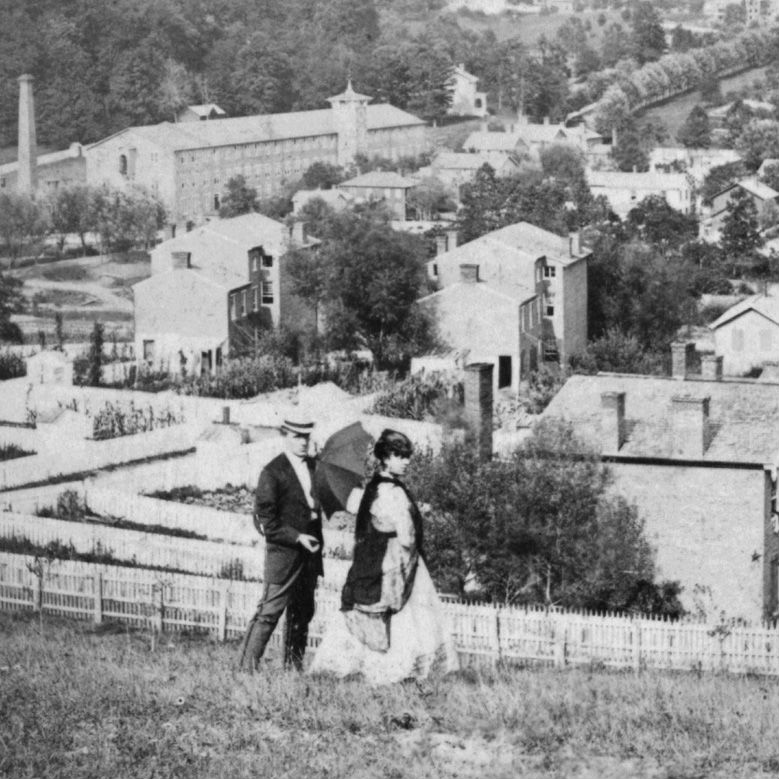

Repurposing Historic Mills: The Jones Falls Tell-All

It’s easy to be surprised by the history in your own backyard, even if you’re a historic preservationist. Nathan Dennies, the chairperson and founder of the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance, joined Nick to trace the history of Baltimore’s iconic Hampden-Woodberry neighborhood, including the many recently re-purposed historic mills, Baltimore’s famous “Avenue,” and the Jones Falls river. The area isn’t just home to Baltimore’s famous HonFest, it’s Preservation Maryland’s home as well. This is PreserveCast.

Introduction

[Nick Redding] It’s easy to be surprised by the history in your own backyard even if you’re a historic preservationist. Nathan Dennies, the chairperson and founder of the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance, joins me to talk about his group’s effort to save the stories and places of Baltimore’s own Hamden-Woodberry neighborhood. We trace the history of the many historic mill buildings that have been repurposed along the Jones Falls as well as Nathan’s predictions and hopes for the future of one of Baltimore’s most iconic neighborhoods. Hampden-Woodberry isn’t just home to the Baltimore HonFest. It’s also Preservation Maryland’s home; and this is PreserveCast.

From Preservation Maryland Studios in the historic podcast District of Baltimore, this is PreserveCast.

[Nick Redding] This is Nick Redding, you’re listening to PreserveCast. We’re joined today in studio here in Baltimore by Nathan Dennies, who is the chairperson and founder of the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance, a volunteer lead community preservation group, whose mission is to save the stories and places of the Hampden-Woodberry neighborhood. Nathan works for AIABaltimore and the Baltimore Architecture Foundation where he manages communications and public programs. But his true love is the Hampden-Woodberry neighborhood where he moved nearly six years ago. And he’s currently working with Preservation Maryland as well as Baltimore Heritage, the citywide preservation group, to create a wayfinding signage plan and exhibit for the historic mill locations in the Jones Falls Valley. Nathan, it’s a pleasure to have you here with us today.

[Nathan Dennies] Thank you, Nick.

[NR] So why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself. It’s always fun to hear about how people get involved in history preservation, architecture. And you’re involved in all of those. So what got you interested in this kind of stuff?

[ND] Well, my final year in college I took an internship with Baltimore Heritage working on their Explore Baltimore Heritage website and app. What I was doing was researching buildings around the city and writing stories about them. And I fell in love with it. It was so much fun. And then I got involved in Hampden when I moved here about six years ago. And I noticed there were all these great historic buildings and we didn’t have any stories on Explore Baltimore Heritage. So from there I really started getting involved in looking into the history of this particular area.

[NR] And so where did you grow up? Are you from Baltimore?

[ND] Yeah. I’m from Baltimore County up in Cockeysville.

[NR] Okay. So you grew up in the area. You’re a lifelong Marylander. Now you live, of course, in Hampden. So we’ve talked about it. But for those people who aren’t from Maryland or perhaps have never been here, how would you describe what is Hampden-Woodberry? What is that sort of neighborhood look like?

A Brief History of the Jones Falls

[ND] Yeah. Well, it was originally part of the county. So when it was established in the 1840s it was way outside in the country relative to the city. And it remains fairly suburban and it still has a very village-like feel even though it’s part of Baltimore City in the North of Baltimore. And it’s part of valley where a stream called the Jones Falls runs through. And the Jones Falls was a power source for all of the mills that were located in the area.

[NR] And so for someone who’s never been here, describe the kind of architecture that you’ll see in this part of Baltimore. Because people think Baltimore rowhouses, we have some of that and we have other things, too, here in this neighborhood.

[ND] It’s very rural in terms of the architecture. There’s the mill building, which are industrial factories. And the homes that were built for the workers, the historic ones, are these gorgeous Gothic revival duplexes with the gingerbread on them and front and backyards. So it has this almost idyllic feel to it although it’s in the heart of Baltimore City.

[NR] And the industry is sort of central to the story. And I should also mention for people listening we’re actually recording this in the Hampden neighborhood. We’re in one of the old mills. Preservation Maryland’s offices are located in the old Meadow Mill, which is a nineteenth century mill that has been repurposed into office spaces now. So we sort of sit in the center of this industrial area. But describe what it was at it’s heyday because there is really very little heavy industry left in this neighborhood anymore. The buildings are here but what was it like back when it was really industrial?

[ND] When it was really industrial there were about 4,000 people employed working at the textile mills and so we’re in one of them, Meadow Mill. And there were also the Mount Vernon Mills, just a little bit south from here. And also Woodberry Mill, which is just across the street. And so it’s a huge set of industry, one of the largest centers of industry outside of Baltimore City. There was also the Poole & Hunt Ironworks across the railroad tracks, too, which employ 800 people. So this was an area of really heavy industry and the neighborhood itself grew out of the industry because the textile mill owners had to bring in a working population to work in these mills. So they went out to the counties, went to Pennsylvania and the Appalachian region to find workers and they had to build housing for these workers to live in.

[NR] And so how long did that last? How long was it truly industrial in this area?

[ND] It really began in the 1840s. There were some industry in the late-eighteenth century with some flouring mills, but it was all very small. But it really took off beginning in the 1840s and then its heyday lasted until about World War I, which is when things really started to drop off and the industry began moving either further south where labor was cheaper or overseas.

[NR] And so for people who think of Baltimore and think of some of those tough years in the late twentieth century that the city went through, did this neighborhood go through those? Did it miss some of that? The industry kind of fell apart and these buildings went vacant. What would you have found if you here in the late 1970s, 1980s?

[ND] It was hit really hard here. After the textile mills began leaving in the early 20th century, the industry was replaced with new industries so we got – London Fog was one of them, made the signature raincoats here – and in the 1970s the textile mill industry has completed evaporated. The last textile mill closed down in the 1970s and people for generations here worked in the mills, that was the only work that they knew. And so people had to go outside of Hampden and find work say at Sparrow’s Point, if there was anything over there. But the entire neighborhood itself depended on that industry.

The Avenue, which is the main street of Hampden, catered to the working class population. So when people lost their jobs they were no longer working the Avenue fell on hard times, too. And so there was a large amount of abandonment. There was also a lot of drug issues, kids who weren’t able to find work. And the Avenue was in really difficult times in the period of 1970s. And what brought it back was in the ’80s new merchants started coming into the neighborhood opening up quirky, sort of artsy stores and cafes and this new population brought Hampden back and it established this new identity that we have today, which is like this quirky, hip main street.

[NR] Yeah. I’m curious, so people who aren’t familiar with the Avenue now it is sort of this quirky, hip main street with a lot of weird things and fun places and good food and all that kind of stuff. And, of course, we have the Baltimore Hon that goes along with all of this. Do you want to tell our listeners what that is?

Hampden-Woodberry’s Recent Redevelopment

[ND] The Hon thing came out of Cafe Hon, Denise Whiting. She created this event called HonFest, which was celebrating this… It’s not really particular to Hampden. It’s more of like a general Baltimore thing of the working class woman with the big beehive hairdo who refers to people as a “hon” [laughter] and wears ridiculous makeup and usually… like a waitress in a diner somewhere.

[NR] Yeah. And so there’s this sort of quintessential Avenue kind of fun, I mean, sort of a quirky weird thing. And it’s an annual festival now, too, right?

[ND] It is, yeah.

[NR] Yeah. So the mills themselves, they fell on hard times. And then, in the late 1980s some developers start moving in –

[ND] That’s right.

[NR] – and thinking about reusing them. What’s the first to be re-utilized and what do we have today now if you were to come to this mill valley?

[ND] The first, I believe, was Mill Centre. And then shortly after that Meadow Mill, which we’re in right now, was renovated and then Mount Washington Mill. Those were the first three redevelopments of the Mill buildings. And then it really picked up within the last decade or so when Poole & Hunt was renovated after that terrible fire in the ’90s. It became Clipper Mill. And then, within a span of a few years, we got Union Mill, which is across the street, and Mill No. 1 and Whitehall Mill. So we’ve been through this renaissance recently of these buildings being reused and converted into these great mixed-use developments, offices, apartments. And also, some industry has returned to the area too with Union Craft with their brewing operation. Now they’re moving into a plant that’s triple the size of where they’re at. It’s a really good time in the Valley.

[NR] I don’t know if we’re – are we back up to the number of workers that we once had before? Do we know? I mean, we must be getting close.

[ND] In terms of industry, no. I mean, it’s mostly smaller industry here today. So Union Craft would be one of the industries. And we have a bakery here in Meadow Mill, which is another one.

[NR] Yeah, but if you added up all the businesses if you weren’t just looking at industry, or at least people living and working and playing down in this area, it’s a pretty vibrant area now.

[ND] It is, yeah.

[NR] And are there any mills left to rehab? Or are we nearing completion?

[ND] There’s one, in particular, which is the Woodbury Factory which became the Schenuit Tire Factory. We were hopeful about that one being redeveloped last year and then it caught fire. And it’s been on the market so it’s fate is still up in the air.

[NR] Yeah. But it’s a pretty – I mean really, it’s nothing short of spectacular what’s happened here in the last 30 years. Gone from total disinvestment and totally vacant to almost 100% in-use.

[ND] Yeah, it makes it easy to be a preservation advocate [laughter].

[NR] Yeah, exactly. Well, why don’t we take a break? And when we come back, let’s talk about your preservation advocacy and the group that you formed and what you’re hopeful for for the future of this neighborhood. And we’ll do that right here, on PreserveCast.

And now it’s time for a Preservation Explanation

[Stephen Israel] Hello, listeners! For today’s segment, I just wanted to give you a quick update on some of the most current preservation news. With the completion of the Public Comment Period in 2017, advocates anticipate that Maryland’s Mallows Bay, the location of a World War I era ghost fleet of ships, may be announced as a national marine sanctuary within the next two years. Back on October 26, 2017, the National Trust for Historic Preservation held a reception for the announcement of the inclusion of Mallows Bay into their national treasure’s portfolio. Their recognition is a testament to the long-term efforts of Maryland archaeologists and advocates to establish the unique site as a national marine sanctuary. One of the last stages of the sanctuary designation process was a period of public comment after which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, will consider the application by the state of Maryland originally submitted in 2014. With all this news, I’m sure you want to learn a little bit more about Mallows Bay. While you can still catch an exhibit about Mallows Bay at the President Woodrow Wilson House in Washington D.C. through February 2018, or you can always go back into the PreserveCast vault and listen to our interview with Dr. Susan Langley, the Maryland state underwater archaeologist, from our third ever episode. But I should probably let you go so you can finish today’s episode first. This is PreserveCast.

[Nick Redding] This week’s episode of PreserveCast is brought to you by Preservation Maryland’s Six-to-Fix. Six-to-Fix is an innovative program designed to help save threatened historic resources across our state. Preservation Maryland invests seed funding, expert professional staff, volunteer time, statewide advocacy, and outreach efforts to move projects towards a better state of preservation. Rather than creating lists of threatened buildings, we’re doing something about it. If you’d like to make a difference, join the cause today by visiting SixToFix.org. There you can learn more about the sites we’ve selected over the past few years and make a donation to help save Maryland’s history and heritage. Together we’re making a difference and saving the very best of Maryland.

Do you have questions? We may have answers. If at any point during this podcast you’ve thought of a question that you have for us or maybe one of our guests, we’d love to hear about it. You can send an email to podcast@presmd.org and we’ll try and answer it right here on the air on the next episode of PreserveCast.

The Formation of The Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance

[NR] This is Nick Redding. You’re listening to PreserveCast. We’re joined today in studio by Nathan Dennies who is the chairperson and founder of the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance. And before we took our break, we were talking about both the history, and the rebirth, and renaissance of this neighborhood and the industrial corridor that supported it in the late-nineteenth and then through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first. And Nathan sort of signed off by saying, “It’s easy to be a historic preservationist around here, because, at least in this neighborhood, we have seen such a renaissance and people really see the value of these places in re-utilizing them.” And I know that you, when you moved into this neighborhood, realized there was no heritage group, there was no preservation group. And so you helped to form one. So why don’t you tell us a little bit about why you did that and what your organization works on?

[ND] I became interested in it while I was interning with Baltimore Heritage. And I had recently moved into the area in Woodberry and I was so taken by the area. I take the Lightrail every day to get from here down to Mt. Vernon, and that path, it’s going along the Jones Falls and you go by all the old mills as you’re going down there. And today was especially beautiful because there was this beautiful fog that was on the Jones Falls with the mills rising above the fog. So it’s like this incredibly idyllic and awe-inspiring trip to get downtown. And it was so inspiring to me. And I wanted to learn more about the history of the area and start documenting it. And I was fortunate to find a group of people who were also interested in it, who were also very talented as well. And we’re all really good friends and that made it really easy.

[NR] And so what do you guys work on? What’s some of the things that you’re doing right now?

[ND] Our first major project was a walking tour brochure of the area focusing on the historic buildings, and we did that in 2014 and we update it biannually. And that really got things off the ground for us. And after that, we started giving walking tours of the area. And more recently, we’ve partnered with Preservation Maryland and Baltimore Heritage on this Jones Falls wayfinding signage project.

[NR] Yeah. And why don’t you tell us a little bit about that? I mean we’re obviously pretty partial to it, so we’ll give you some time [laughter].

[ND] Yeah. It’s covering eight sites along the Jones Falls from Mt. Washington down to Remington. So it begins at Mount Washington Mill, which was the first textile mill built in the area in the early-nineteenth century, and then worked its way down to Remington.

Preserving a Community’s History in the Face of Rapid Change

[NR] The idea I guess is to kind of connect the history of the people who lived here with the places where they worked. Because, like a lot of industrial areas that have changed over time, this area nowadays… you have so many people moved in, who are new to the area, who have no concept of what was here before them or how the neighborhood related to industry. You kind of lost that connection. You were talking before about how it was sort of the lifeblood of this community and now it’s been severed in a sense. And so the idea is to try and knit that back together, at least with a story.

[ND] Exactly. We have all of these new people moving into these beautiful, new apartments. And they’re drawn to these buildings because of the historic nature of them and so this is a way to connect them to that history and also understand how those buildings connect back into the neighborhood. And one of the reasons we began the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance in the first place was that we realized that Hampden had become this really hip, cool area and everyone associated with the Avenue and all the great shopping up there. But we also understood that there is this great history there that we wanted people to experience as well. We also wanted to make sure that we were capturing the stories of the history of the area as it’s so rapidly changing.

[NR] So you do oral history? Or do you actually interview people? How are you documenting this stuff?

[ND] We do do oral histories; and one of things that we do is we have a regular event where we invite people to come to the library to tell stories about the neighborhood. So people bring in an object, a newspaper article… and they talk about their experience in the neighborhood and their stories of its history. And that’s been a great way to learn from people who have lived here for a long time.

[NR] And so what are the challenges associated with getting this group off the ground? Are there challenges? Continue to be challenges? For people who are maybe around the country in a similar neighborhood where things are going well, it’s sort of changed, and they want to hang on to or at least be able to tell that important story, what are some advice that you might give them?

[ND] The biggest challenge for us was creating a structure for the group. We were all really good friends and so it started with us just sitting around and talking a lot. And then we had to figure out how do we actually do this stuff? We were very fortunate to partner with Baltimore Heritage. And they’re a 501C3 non-profit who was able to act as our fiscal sponsor so we didn’t have to go to through the process of becoming a 501C3 ourselves. So we got that benefit out of that. And I think another challenge is volunteer management. We’re all working as volunteers and we have to be respectful of each other’s times and commitments. And so it’s that balance of wanting to do all these great things, but also understanding that there is only so much you can do. I think that’s a really key part of any community organization is volunteer management.

The Future of the Jones Falls

[NR] So the future of this Jones Falls Valley, we have sort of repopulated with a different mix, it’s a different character. It’s offices and apartments and restaurants and things like that. What do you see the future of this place being? What are some things that you’re hopeful for? What would you like to see happen? What’s next? We’ve rehabed a lot of buildings but they’re still more work to do. Where does Nathan see the Jones Falls doing?

[ND] There needs to be a master plan for the Valley. If you’ve traveled on Falls Road before, it’s very narrow, almost country-like road where cars are competing with cyclist and now pedestrians. And something needs to be done with that corridor to make it more accessible to all different types of users. And we’ve been working on master plans for the Jones Falls for the past 100 years beginning with Olmstead. There’s always been this plan for this great park as part of the Jones Falls and it comes around every, almost every decade or so. And now people are again are interested in doing something with the Jones Falls Valley, especially looking at the Falls Road corridor.

[NR] So are you optimistic for that? You kind of sarcastically mentioned that this happens, it’s been happening for the last 100 years. Every 20 years we get around and put together a nice master plan and then we wait 20 years and put together another one. Is there anything different that’s going to happen this time?

[ND] I am optimistic. The big difference today is that in the past it was industry that was here, and so here now people are actually living along the corridor. And so now you have all these people who are living here, they’re going to demand a better quality of life. Whereas before, the industry was really against turning the Jones Falls into a park. They wanted to keep it industrial. And now the industry is gone and we have people who want it to be a livable place.

[NR] So that’s a big thing that’s sort of on the to-do list. And I presume the Heritage Alliance will be involved in that and want to make sure that the culture and history and heritage of the place is a part of that planning process.

[ND] Exactly. And we’re also very interested in the environment and making sure that the Jones Falls is being cleaned and well-kept. Unfortunately, we had an oil spill somehow. A truck turned over and spilled a bunch of oil in the Jones Falls a few weeks ago, so some setbacks but… [laughter].

[NR] Yeah. And there’s also an issue with sort of raw sewage.

[ND] Yeah.

[NR] There’s no delicate way of saying that but just like a lot of urban waterways, this particular neighborhood – and this is a story that I’m sure is similar all across the United States – deals with lack of investment and wastewater and stormwater runoff and we end up with E.coli jumps in the Jones Falls, which is not good for anyone.

[ND] Yeah. Yeah. Every time it rains it seems like hundreds of millions of gallons end up going into the Jones Falls. I am optimistic for the future of the Jones Falls. I mean Baltimore is part of a consent decree, but the city has to get its act together in terms of pollution. So hopefully we follow through with that. And, I mean, we’ve been talking about a swimmable harbor for a long time. It doesn’t seem like that’s happening anytime soon but [laughter] –

[NR] Yeah. I don’t know if I want to dive in just yet but [laughter], I’ll be right after you, Nathan. You know the other question I want to ask you about… so we’ve been talking about the neighborhood and then the industrial valley that’s sort of in the middle of all of it. But running like a ribbon through the middle of it is an interstate that kind of skirts through and it, actually, covers up part of this Jones Falls that you’re talking about, and sort of caps it almost. Or at the very least keeps it very dark all the time, which is a sad decision that was made in the mid-twentieth century. What do you think about the future of that? It’s called the Jones Falls Expressway, if people aren’t familiar with it, I-83. A lot of other communities all across the country propose the idea of daylighting water that was covered up by these things or getting rid of these massive interstates that kind of cut through these neighborhoods. Has there ever been discussion about that? Do you think that that could perhaps be something that will happen in the future? What do you think about the future of that interstate that runs through the middle of your beloved neighborhood?

[ND] Well, we’re fast approaching a point where the city does have to figure out something to do about that because it’s been around now for over 50 years. And, eventually, we have to decide, “Well, do we repair it? Or do we tear it down?” I’m of the mind that we tear it down. The Jones Falls is such a… could be such a beautiful asset for the city. And also, I mean, even people in Baltimore City don’t realize that the Jones Falls actually goes all the way through the city and dumps into the Harbor, and that’s largely covered up by a conduit. So it would be great if the conduit was also removed and we had this beautiful almost-canal. Jones Falls, that was a real asset for the city. But it’s a pie in the sky idea right now.

[NR] Has it ever been proposed?

[ND] It has.

[NR] Has anyone seriously talked about it?

[ND] It has been proposed. Well, now more than ever the daylighting, especially removing the Jones Falls Expressway downtown, has been getting some political legs. But in terms of removing all of 83 in the city and to be moving the conduit, that’s a bit further out I think.

[NR] Yeah. Something to consider, something to work on.

[ND] Yeah.

[NR] And so if people want to learn more about the Jones Falls, they want to learn more about the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance, how could they find more about that? Where would you start to send them?

[ND] The best place is on our Facebook page. If you go to Facebook.com/GreaterHampdenAlliance, you’ll find us there. That’s where we post all of our updates, and if you want to learn more about the signage project, you can go to Preservation Maryland’s website and go to Six-to-Fix and find our project there.

[NR] So, Nathan, as we move to our conclusion here, the toughest question for any preservationist: your favorite building or place. We’re excited to hear where this goes.

[ND] So I’m going to be bad and not choose a Hampden place.

[NR] I think that’s probably actually good for you because there’d be complaints otherwise, I think.

[ND] I’m going to go with the Evergreen Museum. It is one of the most interesting, unique places I can think of.

[NR] So tell people about it who aren’t familiar with it. Where is it? Who lived there? What’s the story behind it?

[ND] It is a mansion for the Garrett family. The Garretts were the barons of the B&O Railroad, the first railroad in the country. And one of their family members got hold of a Greek revival mansion in North Baltimore, which at the time was just basically countryside. And they converted it into this much more modern and almost quirky mansion where – my favorite character is the woman of the house, Alice Garrett, who was a real eccentric and big art collector. If you walk into the house, you can see this massive painting of her dressed in this Spanish outfit with this wide smile on her face so it’s all about her. And one of the coolest things about the place is that it has a personal theater that was designed by Leon Bakst who was one of the designers for the Ballet Russes. And so the Russians would love to get their hands on this theater. And she would perform a one-act show for her guests, so [laughter] Leon Bakst would design her outfits, and she would force anyone to come and watch her perform.

[NR] It sounds a lot like our office. I often force people to watch my one-act show, so…

[ND] And also, it has a gold-plated toilet.

[NR] Is that right?

[ND] Yeah, it does.

[NR] Okay. I was not aware of that. Is that Baltimore’s only gold-plated toilet that you’re aware of?

[ND] That I’m aware of.

[NR] But we never know, and that’s why PreserveCast exists, to find out these answers to these questions. Well, Nathan, it’s been a pleasure to have you with us here today. Thanks for all the good work that you’re doing and look forward to talking with you again in the future.

[ND] Thank you.

Credits

You don’t need to open a history book to find us and available online from iTunes and their Google Play Store as well as our website: PresMD.org. This is PreserveCast.

This podcast was developed under a grant from the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training, a unit of the National Park Service. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Preservation Maryland and the Maryland Milestones Heritage Area and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Park Service or the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.

This week’s episode was produced and engineered by Ben and Stephen Israel. Our executive producer is Aaron Marcavitch. Our theme music is performed by the band Pretty Gritty. You can learn more about them at their website: PrettyGrittyMusic.com, on Facebook, or on Twitter @PG_PrettyGritty.

To learn about Preservation Maryland or this week’s guests, visit: PreservationMaryland.org. While there, you can check out our blog and learn about what’s current in historic preservation. We’re also on Facebook, Instagram, Flickr, and Twitter @PreservationMD. And of course, a very special thank you to our listeners. Keep preserving!

Show Notes

Preservation Maryland has teamed up with Nathan Dennies and the Greater Hampden Heritage Alliance to install professionally-designed interpretive signs at several of the mills along the Jones Falls. Thanks to funding from the Baltimore National Heritage Area. They will be ready for viewing in Summer 2018.

Previous episode